As a man of a "certain age" (47), I clearly remember the 2000 presidential election. Despite the uncertainty that lingered for weeks as multiple vote recounts commenced and we waited to see if Bush or Gore would be number 43, people kind of just "got on" with their lives. Yes, individuals were very insistent that their candidate should get the coveted spot, but I don't remember knock down, drag-em-out arguments. The situation was fodder for a lot of discussion and even humor; I remember a skit on SNL when Bush and Gore decided to "both be president." It was a riff on "the Odd Couple" and people from both major parties actually laughed about it.

In reality, when the recounts were done, one candidate admitted defeat and got on with his life. The other became president. The process was civil and dignified, albeit LONG. At some level, most people accepted that their team lost and things got back to normal. There were some rough spots between friends and family members, but nothing on the scale of what we've seen this year.

So what's the difference? Why are things so much more brutal and divisive than before? Why are we so quick to judge people as 0's or 1's as opposed to more nuanced decimals and fractions? Social media bears a large part of the blame.

Yes, I know we've all heard it before. Facebook destroys friendships. Twitter is a dumping ground of political angst. We know that too much social media is bad for us, but the bigger question is why. I think some of the answer lies in science fiction.

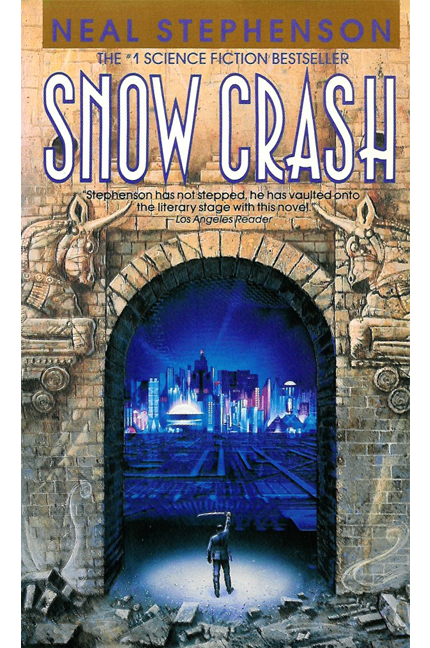

Fans of 90's/2000's cyberpunk will certainly remember Neal Stephenson's classic Snow Crash:

The following synopsis is a vast oversimplification of Stephenson's brilliant work, but the story centers around a computer virus that manages to jump from hardware to human beings. Imagine a computer bug that could infect people based on people who were geared to receive it. In this case, the virus affected computer programmers because they had been trained to see "code" whereas the uninitiated (non-computer programmers) were somewhat immune. Directly stated, the virus could only affect you if you'd been conditioned to see it.

In many ways, that seems to be where we as a culture are. Depending on what statistics you follow, about 70% of Americans are Facebook users (

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/16/facts-about-americans-and-facebook/); to use the Snow Crash analogy, almost all of us, at some level, have become indoctrinated to the platform. Social media does not work well with most people in "long form." As a result, posts are short, and content is compressed. In other words, the key points get amplified and the subtleties and nuances get crushed...compressed, some might say.

There's a reason that many musicians are leery of using "compression" on their instruments. This device is used to manage sound levels, but can sometimes crush the ultimate tone. For example, when I play bass, sometimes I finger pick and other times I slap or tap:

When I hit the strings harder, the sound gets louder. A compressor evens out all of the volume levels to keep things more consistent and easier to manage. When used properly, the compressor keeps things from getting too loud. However, a compressor can also make EVERY sound too loud or only amplify the loudest noises.

Social media often acts like a compressor. The most inflammatory statements (slaps and taps) gain volume and momentum while the nuance and sensitivity (subtle solos and harmonics) get lost in the shuffle. Our online conversations are reduced to the most base and loud things we have to say.

Here's where it gets really ugly. In the same way that the virus in Snow Crash jumped from computers to people, our "new" way of interacting has made its way into the real world. All of the sudden, those who don't agree with you are living up to the memes that stereotyped your opponent's political beliefs. You no longer need to explore your friends' views, backgrounds, or life perspectives because they have been quickly compressed, distilled, and laid out for you in statements that can be read in 15 seconds or less. The people we love have been judged by what media we consume.

I can admit that I've been guilty of this behavior. Lucy Van Pelt has some good advice for this issue:

In "A Charlie Brown Christmas" Lucy advised our favorite round-headed kid that his ability to admit a problem meant that a solution was possible. I hold hope that we can deprogram ourselves from this epidemic of social media invading our physical reality. The remedies are simple in concept but potentially difficult in practice.

Step one: Limit your social media interactions and screen time. Simple, right? Considering how addictive these services are designed to be, it's no simple task. If you are online, avoid (or block) the political content, and unfollow friends if you have to. Unfollowing someone is not erasing them from your "real" life. Consider migrating to less political social media outlets; for example, Instagram consists mainly of dog pictures and funny videos. Such content might make for better use of your scrolling time.

Step two: Have a real-time interaction with a friend with whom you politically disagree. Try a phone call, a Zoom session, or lunch if you're comfortable during COVID. Agree to NOT talk about politics. Think about the reasons you're friends in the first place. Do a few of these sessions before you attempt to engage in any kind of political discussion. Remember, you're de-conditioning yourself...and potentially your friend.

Step three: When you're ready (and if you're willing) ask your friend why they feel the way they do. Why are some issues so important to them? How do they believe their candidate will deal with these points? Agree to keep the conversation non-judgmental. Set ground rules against name-calling and "inflammatory" language. I know this sounds crazy, but it can be done.

We should not feel compelled to agree with everything our friends believe, but we should be willing to listen and to regard them as three-dimensional, complex human beings. People are not easily quantified based on their party affiliation or voting choices. The people we care about vote based on pride, fear, opinion, logic, and gut feel....sometimes in direct opposition to their actual best interests. We are complicated, and so is our reasoning when we draw the curtain in the ballot box. Perhaps if we spend more time interacting in the real world, our friends might take some of our perspective with them as part of the process.

The votes are still being counted; make good use of the time.

Comments

Post a Comment